A visit to Valensole

Flying Saucer Review – Vol. 14, n°1, January-February 1968

by Aimé Michel and Charles Bowen

The tumult and the shouting had long since died when we contrived to visit the small Provencal town of Valensole. It seemed that the startling event in the lavender field which occurred on the morning of July 1, 1965, had been forgotten, until we reminded ourselves that the official reaction to the Marliens marks[1] had shown otherwise.

Back in 1965, M. Maurice Masse, the witness — or victim, if you prefer it that way — had been left shattered and dazed by his alleged experience with the humanoid occupants of the “saucer”, and from the hammering he received from journalists, police and other official investigators, researchers and curiosity-seekers. Rumour had it that he had wearied of the case; that he wished he had never blurted out his bizarre story to the proprietor of the Café des Sports.

As far as we are concerned — and if we here sound callous, it is certainly not with deliberate intent — we can only say we are thankful he was so shocked that he was unable to control either his emotions or his tongue for those few brief moments, for we consider the Valensole Affair to be one of the most important cases in the history of the subject[2].

For the benefit of those to whom Valensole is only a name, we have recapitulated brief details of the case: these appear in an adjoining panel.

We have often wondered how M. Masse had fared since his ordeal. When, earlier this year (1967) we learned of other sighting reports from the district, a visit to Valensole was clearly indicated.

Aimé Michel. What better opportunity than August 1967, some two months and seven weeks after the original landing, when Charles Bowen and his family were visiting France for a holiday?

Charles Bowen. On the morning of August 21, with Aimé Michel at the wheel, an exciting drive over breathtaking Alpine passes and through magnificent gorges, brought us quickly to Digne. There we were joined by Aimé’s brother Gustave Michel, who was accompanied by his daughter Sylvane.

South of Digne, a long and sharply winding ascent took the cars up on to the great plateau of Valensole. I confess my imagination boggled when, from afar, I saw this plateau for the first time, for it looks like the base of some enormous mountain, the top of which had been removed by a scything cataclysmic blow…

BRIEF OUTLINE OF THE INCIDENT AT VALENSOLE ON JULY 1, 1965

On several mornings during June, 1965, M. Maurice Masse and his father, lavender growers of Valensole in the Basses Alpes of France, discovered with growing annoyance that someone had been picking shoots from plants in their field named l’Olivol. On the morning of July 1, 1965, at about 5.45 a.m., Maurice Masse was finishing a cigarette before commencing work on l’Olivol. He was standing near a hillock of pebbles and rakings by the end of a small vineyard alongside the field. Suddenly he heard a whistling noise, and glanced round the side of the hillock expecting to see a helicopter; instead, he saw a “machine” shaped like a rugby football, the size of a Dauphine car, standing on six legs with a central pivot stuck into the ground. There were also “two boys of about eight years” near the object, bending down by a lavender plant.Incensed, Masse approached stealthily through the vineyard and saw that the creatures were not boys at all; he broke cover and advanced towards them. When he was within five metres of them, one turned and pointed a pencil-like instrument at him. Masse was stopped in his tracks unable to move. (Aimé Michel has suggested that he was immobilised by a form of hypnotic suggestion. If it had been muscular paralysis, Masse would have died.)

According to Masse’s testimony the creatures were less than 4 feet tall, and were clad in close-fitting grey-green clothes, but without head covering. They had pumpkin-like heads, high fleshy cheeks, large eyes which slanted away, mouths without lips, and very pointed chins. They made grumbling noises from their middles. Masse will not disclose what happened during the encounter, and says that after a while they returned to their “machine”. He could see them looking at him from inside while the legs whirled and retracted. With a thump from the central pivot, the machine took off to float silently away. At 20 metres it just disappeared, although traces of its passage in the direction of Manosque were found on lavender plants for 400 metres.

When he recovered mobility, a confused and frightened M. Masse rushed back to Valensole. There, the proprietor of the Café des Sports saw him and, alarmed by his appearance, questioned him. Masse blurted out part of his story; the proprietor could not contain himself, and the news quickly broke.

A.M. I suspect my friend’s imagination has been nourished by too much Velikovsky. The Valensole plateau is of alluvial origin. It is a huge deposit of alluvium, gashed later by the valleys which form the surrounding country.

C.B. I bow to Aimé Michel’s intimate knowledge of the geological origins of his beloved Alps.

This unique tableland stands fully 1,000 ft. above the surrounding valleys, and beyond its periphery the Alpine ranges begin to dwindle towards the Mediterranean.

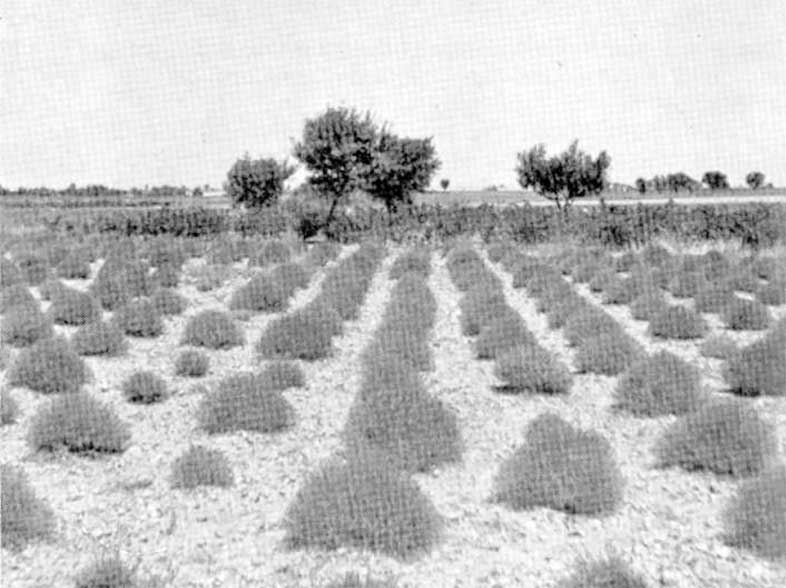

Once up on the plateau, the surface is seen to stretch away as far as the eye can see, and it is covered for the most part with millions of lavender plants which are all arranged in precise rows. The monotony of the landscape is barely broken by the occasional house or hut, a small vineyard here and there, with a few olive trees and an occasional mulberry tree. The sweet smell of lavender pervades the whole of the region.

A.M. The plateau is immense, and although we travelled quickly, there was ample time to discuss many things. In particular I talked of the sighting of an unusual object which had been seen and reported by the astronomers of the St. Michel Observatory. As we approached the village of Valensole, I was on the lookout for a gap in the mountains which we could see at intervals to the West beyond the plateau, for it is beyond these mountains that the Observatory is situated.

Here is the account which I told Charles…

The St. Michel Observatory sighting

Towards the end of September 1965, about three months after the incident at l’Olivol (the name of M. Masse’s field), an astronomer friend of mine informed me of the following fact:

At about 3 a.m., local time, in the night of September 17/18, three astronomers who had just finished work stepped out of the cupola to take a breath of fresh air. The night sky was clear and they were able to identify with ease the lights — very familiar to them — of the various villages, far and near. But towards the ESE — in a direction that they were able to pinpoint with great precision in relation to the mountains — precisely in the direction of the peak marked 1577m. lying to the SE of the village of Aiguine, but much lower down, and on the exact level of the Valensole Plateau, they beheld a large stationary ovoid-shaped, orange-red light. They watched this light for 10-15 minutes without seeing any change in its position or its appearance, nor did it flicker as the flames of a fire would have done. A solid object emitting its own light would have looked no different. The three astronomers wondered what it could be, but none of them dared to suggest that they remain there until something happened and, feeling a bit uneasy, they went off to bed.

I made discreet enquiries of the Valensole Gendarmerie as to whether anything had flown over there that night or any other night before or after the night of September 17 (in case by any chance the astronomers, who had made no notes about it straight away at the time, might have been mistaken by a day or two on the date). I asked the Gendarmes whether there had been any fire or night-time conflagration, or anything similar.

There had been nothing, they said, and no marks of any sort had been found or reported anywhere on the Plateau.

I then spoke about this matter to a physicist friend of mine who is in charge of certain work at the laboratory which the École Normale Supérieure of Paris maintains at Valensole. This friend drew my attention to the fact that this Valensole laboratory, where certain phenomena of the Ionosphere are studied, possesses aerials stretching in a line for a distance of one hundred metres on top of a series of pylons, and that the tops of all these pylons are sometimes illuminated at night by lamps. Perhaps, he suggested, the astronomers might have seen all these lamps bunched together as it were by the perspective? (For the pylons run in an oblique line in relation to the direction in which the St. Michel Observatory lies). A phone call to the laboratory sufficed to give us the assurance that the lamps on the pylons had never been turned on during the period in question.

However, in order to be able to rule out this possibility absolutely, two experiments were arranged. In the course of a good clear night, the lamps were turned on for five minutes and then turned off for five minutes, this being repeated a number of times. Then, on another night with excellent visibility, the lamps were turned on for half an hour, without break. On neither of these occasions, and even with the help of powerful binoculars, was anything glimpsed of the lamps.

These two experiments proved that the Valensole laboratory of the École Normale Supérieure is invisible from the Observatory, which fact it is in any case easy to establish by crossing the Valensole Plateau, from which the Observatory’s domes (the largest in Europe, and of a silvery-white colour) are only visible along a quite narrow strip of terrain between the Volx rocks, on the right bank of the River Durance. The field called l’Olivol is precisely in the middle of this strip.

If astronomers with binoculars had looked in this direction on the morning of July 1, 1965, they would have had a perfect view, at a distance of 23 kilometres, of the scene of M. Masse’s experience now so familiar to us, and in that case perhaps we should know a good deal more about it all.

Journey’s end

The account of the St. Michel Observatory sighting saw us almost to the end of the long straight road beside the northern edge of the plateau. Suddenly the road dropped in a long curve, and the cars swept into a typical Provencal village. We had arrived at Valensole, and I for one was thankful to see the tree-lined main thoroughfare with its welcome shade from the blazing sunshine.

M. Gustave Michel — a retired warrant officer of police —went straight to the gendarmerie, where he is well known. We hoped to learn where we could find M. Masse.

It was immediately apparent to me that M. Masse is both well known to the police, and respected by them. There were no jokes. We had to appreciate, they said, that M. Masse was a very busy man, especially at this time of the year: we might find him at the lavender water distillery of which he is joint owner with three other farmers.

We drove on for about half a kilometre from the southern edge of the village until we came to the distillery. He was not there, but was expected to return in a few minutes, so we passed the time of day chatting to one of the other joint owners, and to some of the workmen. They entertained no doubts about the sincerity of M. Masse: we also learned one or two other interesting things before his Peugeot was seen coming down from the village.

I confess I found the conversation in the Provencal accent at times difficult to follow, so I gladly leave the account of the ensuing discussion to my friend, who also has a few things to say about his original meetings with the witness in 1965.

August 1965 interrogations

A.M. I had not seen M. Masse again since August 8, 1965, although many people, including some Valensole residents, had kept me informed of all he had been doing and saying. I found him again just as he was before, as regards his personality, that is to say calm and patient. But, on the other hand, I was very much struck by the complete change in his attitude towards his strange adventure. In 1965 he had appeared anxious, nervous, and on two occasions even distressed. The first time he was distressed — and I even saw his hands trembling — was when I was moving my compass to and fro near his watch, and he saw the compass needle move. “Then — what about me?” he cried. “Haven’t I too been touched by anything? By a ray?”

The second occasion on which he was overcome was at the end of the interrogation by my brother and myself, over an incident which I refrained from publishing at the time but which I communicated to a few people, among them Charles Bowen and Gordon Creighton. Before going to Valensole, on August 8, 1965, I had wished to make a thorough study beforehand of the Socorro case, so I had asked friends to let me have all the data available. Among the documents received, there was a coloured picture of a model reconstituted from the description given by Lonnie Zamora of the object that he had seen. When I was absolutely sure that I had obtained from M. Masse all the details that he had decided to give me, I took the photograph of the model out of my brief-case and showed it to him.

The effect produced on him was fantastic. I had the impression that, on seeing that image, M. Masse was at his last gasp, as though he had just looked upon his own death.

At first he thought that somebody had photographed his machine. When he learnt that this one had been seen in the United States by a policeman, he seemed relieved, and said to me:

“You see then that I wasn’t dreaming, and that I am not mad.”

In 1965, in a more general sense, M. Masse had an air of anxiety and misgiving about his adventure. He did, it is true, affirm to us that: “they were good” and that: “they did not wish to do us any harm.” But he was not in the least bit easy in his mind as to the possible results of the incident so far as he himself was concerned. Moreover he had been knocked off balance psychologically; the incredible experience clearly could not be fitted in with his simple peasant’s way of life.

August 1967 conversation

In 1967 however, we were all struck by his serenity, and it is noteworthy that my brother Gustave who is, in his own profession, well used to sounding out people’s thoughts and feelings, should have declared that he was far more impressed by this new attitude of M. Masse than by his earlier one. The earlier attitude had been that of a peasant, honest and intelligent, it is true, but in no respect whatever any different from any other honest and intelligent peasant who has been subjected to a psychological test. Now, however, M. Masse is a man in whom there dwells a certainty, a man who no longer displays any curiosity as to what folk who have studied the question at great length, like Charles Bowen or myself, might say to him. Here is a résumé of our conversation with him. By résumé, I mean that a desultory conversation is diffuse, repetitious, with lots of expressions like “that’s about it” and circumlocutions and so forth, all of which when put into writing can be more condensed without anything at all being lost. I have merely condensed what was diffuse.

My brother and I had started off by saying we were glad to see him again and by the usual polite remarks, including mention of this year’s drought, and the lavender crop, and so on. And then I told him who Charles Bowen was.

Then I said to M. Masse: “I have always had the impression that you did not tell me everything.”

“That is true,” he replied. “I did not tell all. But I have already said too much. It would have been better if I had kept it all to myself.”

“Yes,” I said. “But all the same it is very important. Look, there are thousands of people who are seeking to know and to understand. It is necessary to help them. You must go through with it, since you have begun, and not withhold any more of it inside you.”

“Yes,” he replied. “It’s very important, but I can’t explain anything. All that I could do would be to say things that would not be understood. You have to have undergone it to understand it.”

“How do you know that?” I said. “Just try.”

“Monsieur,” he replied. “What I have not told you, I have not told anybody, not even my wife, and nobody will make me tell it. Do not insist on it, and let us say no more about it.”

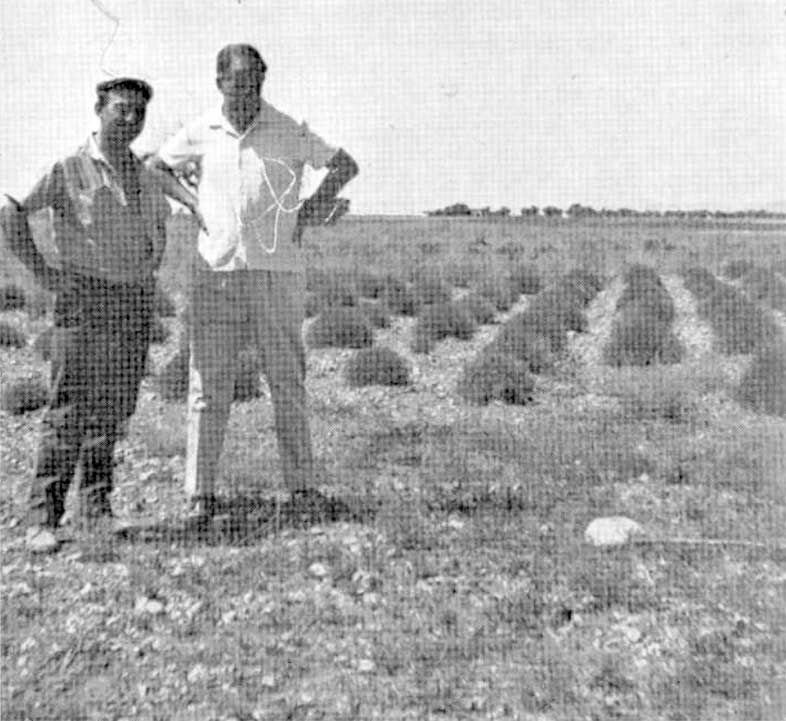

As all this had been going on at his Lavender Distillery, he then added: “Come along if you like, I will show this gentleman (Mr Bowen) the Olivol field.”

So we got into our car and followed him.

The landing site

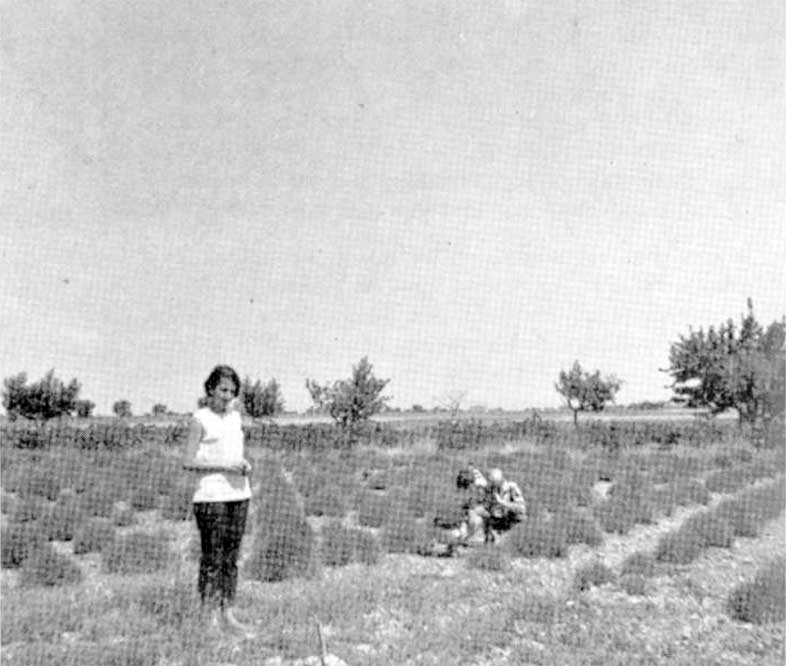

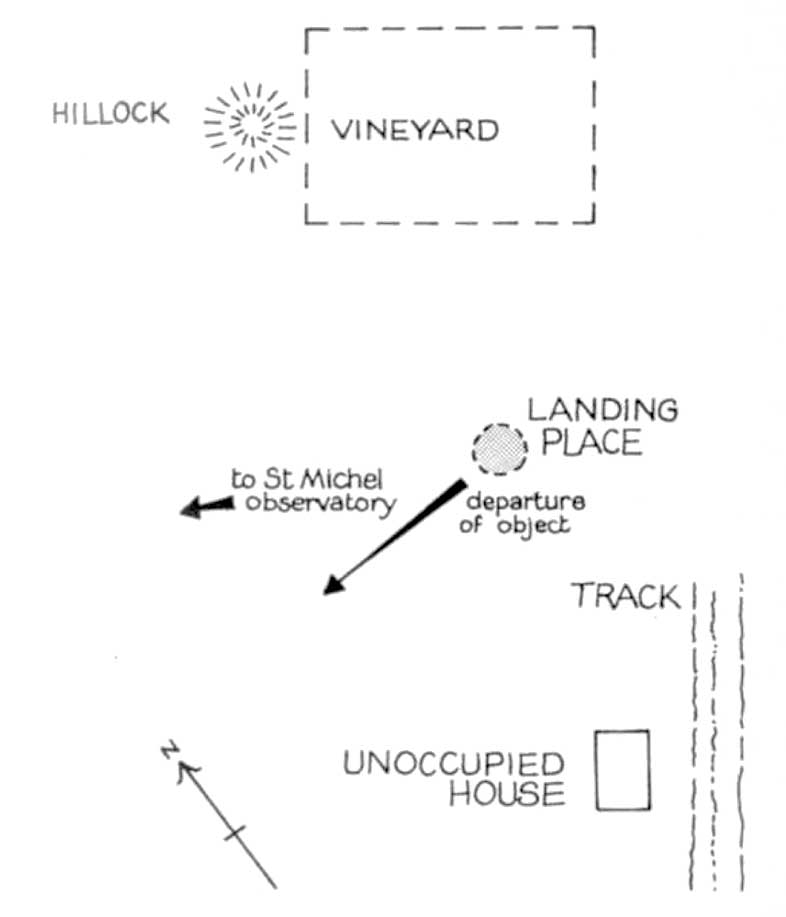

C.B. For one who was very busy, M. Masse was indeed generous to spare us so much of his time. He led the way back through the village and up on to the plateau, where we left the main road, and branched off along a dirt road. At about 1 km. from Valensole, we parked the cars beside a small unoccupied house at the edge of the field called l’Olivol.

The immediate impression that one gains is, as always, the vastness of the place. L’Olivol is but a tiny fraction, a tiny corner of the gigantic whole. However, I soon began to discern features that I remembered from past articles and sketches. There, for instance, was the vineyard with the colline de cayoux — a large pile of pebbles and other rubbish — just beyond. Frankly I was a little disappointed with the vineyard, for I had always imagined a large plantation with abundant growth through which M. Masse had silently approached his quarry. The plants in the vineyard which I saw, and that includes the few trees, would have afforded a man the size of M. Masse practically no cover. Anyone in that field would have been well aware of his approach.

Which brings me to the next point: the actual site of the landing was more than the length of a cricket pitch (22 yards — a useful standard for measurement) from the nearest point of the vineyard. I would say it is nearer 25 yards away, and if, as M. Masse claims, he got to within 5 metres of the creatures before they stopped him, then he must have covered some 15 to 20 yards in the open.

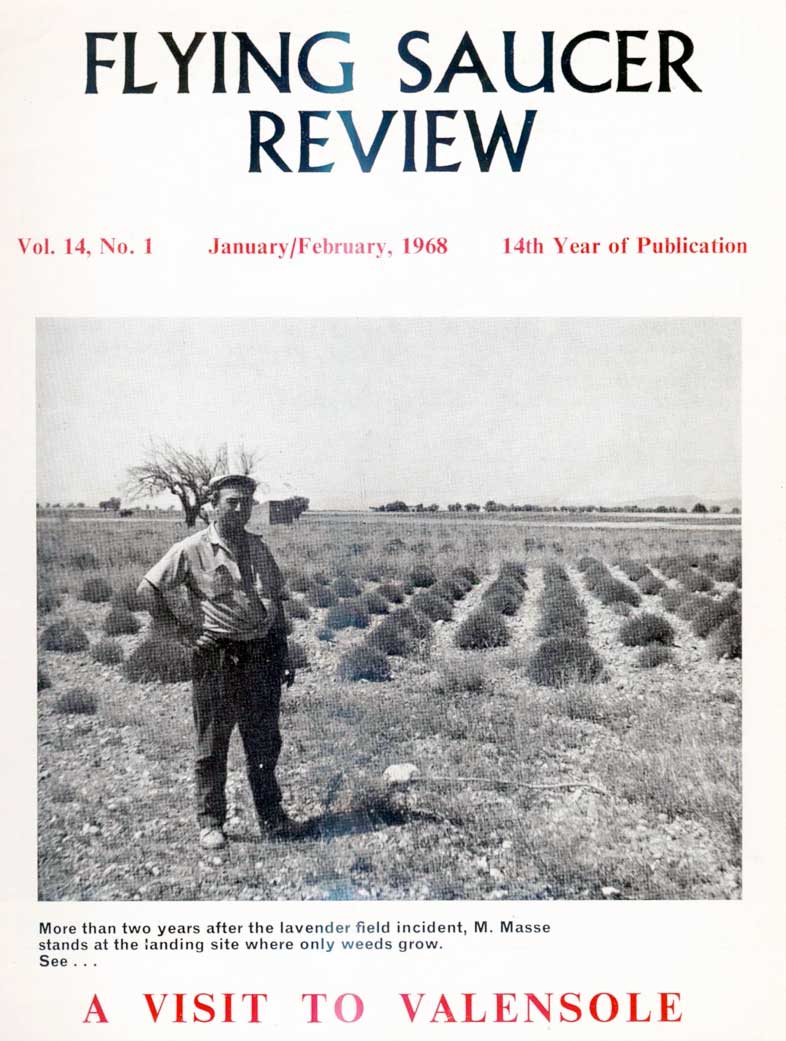

I can say this with some certainty because the actual landing site is still clear for all to see. It is a circular area of land in the midst of the precise rows of lavender plants, where nothing is growing other than a few sparse weeds. The area is about 3 yards in diameter, and around the perimeter a number of lavender plants are stunted and withered-looking. They are certainly not healthy plants like those in the rest of the field.

There are no longer any signs of the marks left by the object. M. Masse told us that he had re-ploughed the area, and replanted it: all the new plants died. The straggling weeds, so Aimé Michel tells me, are trifolium melilotus.

The little unoccupied house, beside which we had parked the cars, is another thing which I cannot remember being mentioned in the previous accounts. Again, the hillock of stones and soil, behind which M. Masse was smoking a cigarette beside his tractor on the fateful morning, is very much closer to the end of the vineyard than I had earlier imagined.

When one looks from the landing site towards the little house, one is facing towards the south-west. According to M. Masse, the machine took off towards the West, that is towards Manosque: in that direction there is just a small wooden hut, otherwise the ground is wide open. If the machine had been travelling very, very fast — instead of disappearing, according to M. Masse — it could still have been seen going on its way, even if only for a split second or so. British readers who do not know France may not be aware that the fields in that country are rarely enclosed by hedgerows like those so familiar to us. Instead, the boundaries are marked by tracks, or low wire fences. Naturally, this adds to the sense of spaciousness. And up on the Valensole plateau one has unimpeded vision for very great distances.

While I was taking a few photographs for the record, Aimé Michel engaged in another interesting conversation with M. Masse. I had also noticed that he had been more than a little taken aback by the layout and dimensions of the field.

A mistake explained

A.M. On arriving at the spot, and looking at the scene, I had the biggest surprise of the whole day. The vineyard was not at all as I had remembered it (or thought I remembered it). It was at least four times farther away from the landing site than I had shown it to be in the sketch with my article in Flying Saucer Review for November/December 1965. It took several weeks of mulling over my notes before I found the origin of this incomprehensible mistake. Here it is and, as will be seen, it is not without importance:—

In August 1965, I had first of all paid a visit to Captain Valnet at the Digne Gendarmerie. There, I had read the report on the first investigation, and with it there was a detailed plan of the site together with photographs. Valnet had warned me that Masse, encouraged by Oliva, had admitted having got very near to the machine and to its occupants.

I made a copy of the plan of the site while I was at Digne, and then I went to Valensole where, without Masse being present, I started off by hearing Oliva’s account. After which we went to the lavender distillery where, in the presence of Oliva and of my brother Gustave, Masse gave me the story as we have heard it from him. Then M. Masse’s father took me to l’Olivol field, whence I returned, in the afternoon, to the distillery to put a few additional questions to M. Masse.

After I had got back to my own home, which is about three hours’ travelling from Valensole, I went to bed and was ill for two days. This brief and intense illness (a high fever) puzzled me, but there are no grounds permitting us to attribute any particular significance to it. When, later on, I began to draw up my account of my investigation, I found to my annoyance that I had lost the little sketch-plan of the site which I had made in Captain Valnet’s office, but finding, on reading through my notes, that my memory had not deceived me in any respect, I thought that I could make the sketch-plan again from memory. Now, as it happens, this plan was wrong. Why? The explanation is as follows:—

M. Masse having told me, most carefully and in the greatest detail, how he had approached the machine and its occupants across the vineyard, I unconsciously made the deduction that he would not have been able to approach so close to them in open terrain without their being alerted, and consequently the image of a vineyard reaching to as far as a few metres from the craft had taken root in my mind without my being aware of it. Well now, this implicit reasoning was correct, as Charles and I were able to establish on the spot. It is in fact totally impossible to emerge from the vineyard and get to as far as a few metres from the landing site without being seen.

But this alters the whole deeper interpretation of the incident. If the two beings remained squatting there without moving throughout the whole of the time that it took for M. Masse to cover about fifteen metres, when they could not have failed to see him coming, this means that the whole thing was premeditated. This detail, of capital importance, lends fresh weight to the hypothesis that the depredations perpetrated in the Olivol field during the last few nights of June were in fact designed to arouse the curiosity and the vigilance of M. Masse[3].

Final conversation with M. Masse

But now let us return to 1967. At the Olivol field, we asked M. Masse to start telling his story once again. This he did, without producing anything new. Hoping to encourage him to go further, I tell him the story of Barney and Betty Hill, which he does not know. He listens to it, visibly uninterested by it, and makes this comment:—

“If those people say that they were forced, it is not true.”

“Why?” I asked, somewhat surprised.

“Because they don’t force anybody. If those people had said No, if they had said ‘I don’t want to’, ‘they’ would have left them in peace.”

“Why are you so sure of that?” I asked.

“Because I know.”

“How do you know?”

“I have told you that I will say nothing more about what happened to me. I will die without telling anyone. Do not insist. But if I talk like this about those Americans, it is because I know that that’s how it is.”

At this point there occurred an incident which I think will interest all scholars of Ufology. When I asked him if he knew “them” sufficiently well to be able to affirm categorically that “they” never forced anybody, this was his reply:—

“To say that I know them, no. But there are things of which I am sure. For example, I know when they are about.”

“What do you mean?” I said.

“This: that on several occasions something in me has told me: ‘they aren’t far off’, and then I actually have either seen something in the sky, or I have learnt afterwards from the newspapers that something had happened. For example, during the famous night of July 17-18 last[4], I was outdoors and was asleep. Suddenly, I was awakened by the impression that ‘they’ were going to show themselves, and I began to look up at the sky, and twenty minutes later I saw the thing go over. That has happened to me several times.”

Very intrigued by these statements, I tried to get more details from him, but with no useful result. M. Masse takes no notes and makes no effort to remember what does not interest him. And our scientific curiosity does not interest him. The concrete details seem futile to him. What seems essential to him is the mental relationship existing between these beings and men. But in him this relationship is felt, rather like a religious concept.

As regards the night of July 17-18, this (alleged) premonition would have an altogether special interest should it ultimately be established that it was indeed a Vostok. We can engage in various speculations about it, all as fascinating as they are unprovable.

Distant cupolas

C.B. M. Masse took his leave and returned to his work, and the rest of us pottered around taking photographs. Suddenly Aimé called me and pointed to the WNW. In the distance, far beyond the edge of the plateau, there was a range of mountains. These are not very high, being mostly of the order of 4,000-5,000 ft. At one place in the ridge there is a narrow gap, and through this, even without the aid of binoculars, we could see a few white, regularly-spaced spots. These are the famed cupolas of the St. Michel Observatory. It was immediately obvious that one would not have to move very far from the field l’Olivol before one could no longer see the cupolas.

Creature report

I was intrigued by the unoccupied house which can be seen in one of my photographs, and fell to wondering if this was the one connected with an account published by René Fouéré in the GEPA bulletin, Phénomènes Spatiaux[5].

In this article, it was told how one of their members, a M. Francois Peyregne, had visited Valensole early in 1967. He described the plateau as looking like “an immense platform for interplanetary manoeuvres”.

By far the most interesting piece of information discovered by M. Peyregne was that at the end of January 1967 five local people found a little man in an empty room in an old farmhouse that was being repaired. This little creature was reported to be identical with those described by M. Masse, except that he was bearded. The whole party tried to capture the little fellow, and a wild chase ensued. However, it was all in vain, “for something like an invisible force caused him to slip through their hands”, and he escaped through the window. Further pursuit across the countryside proved futile.

According to M. Peyregne, the five witnesses desire no publicity whatsoever, and he added that it would not surprise him to learn that other people in the region had had their own incredible experiences, but preferred to lie low.

Nobody mentioned this story either to Aimé Michel or to myself while we were visiting Valensole, and we had little time in which to pursue it further. However, there is yet another Valensole case which we feel should be recorded. We first heard about it while we were waiting for M. Masse to turn up at his distillery.

A.M. As Charles Bowen has told you, when he, Gustave and I arrived at the distillery, M. Masse was not yet there. Five or six men were busy around the machines. We seized the opportunity to talk to them about M. Masse, who, in what they said about him, was described to us once again as a respected man whose good faith is doubted by nobody.

Out of the past

One of the workmen present told us that when he himself was a child he heard an old peasant couple tell how, one night, they had seen a luminous, red, egg-shaped object descend from the sky, settle quietly on the ground, remain there about a quarter of an hour, and then rise up into the sky again and vanish. The two old peasants are long since dead. The thing happened before the First World War (I believe the man said it was — or may have been —1913 . . . C.B.).

The place where it landed was right next to l’Olivol field.

M. Masse having in the meantime arrived at the distillery, we left the workman in order to go to l’Olivol, promising ourselves that we would return and question him later. But, on our return, we were told he had finished his work and nobody could tell us where to find him. I hope to be able to gather more details on this report on another, future trip to Valensole.■

NOTES:

(1) Rifat, A., Was it a landing at Marliens? FSR, Vol. 13, No. 5. September/ October 1967.

(2) Bowen, C, A Significant Report from France, FSR, Vol. 11, No. 5, September/October 1965.

Michel. A., The Valensole Affair, also G.E.P.A. Investigation, The Significant Report front France, FSR, Vol. II, No. 6, November/ December 1965.

(3) In 1967 at Valensole, the Spring was cold and dry, and the Summer was excessively dry. Vines, which are pruned each year, were consequently very low and thin. In 1965 they were tall and thick, and could easily hide a man (A.M.).

(4) The night on which, so some people say, a Vostok satellite disintegrated in the atmosphere over Western Europe, which is indeed possible, but does not perhaps explain all that happened (A.M.).

(5) Phénomènes Spatiaux No. 11 (March 1967).